Spek - specification test framework for Kotlin

Some time ago when I had started recognize the ‘new’ JVM language from JetBrains named Kotlin I was looking test framework for that language which allows me to write tests on Kotlin within my Java codebase (due to the very good integration between Java and Kotlin). After short search I found the Spek - Kotlin Specification Framework.

The idea was simple - to start working with Kotlin more but at the beginning with the test code (long long time ago I had used Spock in order to learn Groovy). Before I move forward I have to say that this post has been written for Spek version 1.0.89. Because it is a young framework you could expect some changes in the near future - be aware of it (at least that was until now for each new version which I was trying).

Before I focus on Spek is worth to say a little more about Kotlin itself. According with Wikipedia:

Kotlin is a statically-typed programming language that runs on the Java Virtual Machine and also can be compiled to JavaScript source code. Its primary development is from a team of JetBrains programmers based in Saint Petersburg, Russia (the name comes from the Kotlin Island, near St. Petersburg). Kotlin was named Language of the Month in the January 2012 issue of Dr. Dobb’s Journal. While not syntax compatible with Java, Kotlin is designed to interoperate with Java code and is reliant on Java code from the existing Java Class Library, such as the collections framework.

From my perspective the first look at Kotlin was very promising. The concise syntax, null safe approach, good interoperability with Java and the fact that behind it is the company which created Intellij Idea force me to deeper look at it.

Though Spek is written in Kotlin is 100% compatible with Java. The specifications could verify new or existing Java or Kotlin code. What is a specification? In simple words it is a test in a more human-readable way. If someone used the Spock, Jasmine or Mocha then won’t have a problem to understand the Spek. Let’s take a look at simple example:

@RunWith(JUnitPlatform::class)

class CalculatorSpec: Spek({

given("simple calculator") {

val calculator = Calculator()

on("calculating the sum of 2 and 2") {

val result = calculator.add(2, 2)

it("should return 4") {

assertEquals(4, result)

}

}

}

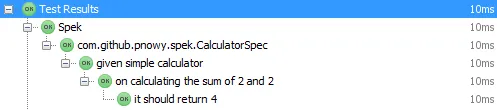

})As you can see on this simple example we have class CalculatorSpec which extends the Spek class. Within the body we could define our specification. When we run the example by Intellij test runner we will see the following result:

That kind of testing is much simpler especially if we are talking about readability of the code. We have some subject which based on some action should either return specific result or execute specific action. That’s why the specifications are used as a ubiquitous language on BDD.

Before we move on the one thing should be explained. The previous versions of the Spek were built on top of the JUnit 4. With final version 1.X the Spek team had migrated to JUnit 5. This change affects the ways how we could run the tests so I will try to explain it a little bit because at the beginning it could be a little confusing.

So let’s start from the JUnit 5. The Spek provides an adequate JUnit Platform test engine which allows to execute the specifications under JUnit 5.

In order to enable it on the project the dependency to spek engine should be added (org.jetbrains.spek:spek-junit-platform-engine:VERSION) and the plugin

to the build tool should be applied (in my case it was junit-platform-gradle-plugin which runs the JUnit5 tests on gradle). So far so good.

The problem appears when you want to run the tests on the Intellij IDEA. Despite the fact the IDEA supports the new version of

JUnit you will not see the run button on specifications out-of-the box. The solution for this problem is a dedicated IDEA plugin.

Unfortunately it has some lacks (like navigation to source via the test tree or possibility to run multiple specs) but I believe that will be fixed on the future.

There is also the possibility to run the specifications by JUnit4 based runner which runs tests on the JUnit Platform in a JUnit 4 environment.

In order to do that you have to mark the specification with @RunWith(JUnitPlatform::class) and you will able to run the test on IDEA.

You will find the examples on the GitHub repo regarding this post.

Please take into account according with Spek documentation support for JUnit 4 is very limited and it also may be dropped in future releases.

The advantage of running by the JUnit4 within IDEA is a test tree which is displayed during test execution. As I mentioned the IDEA plugin has the problem with it right now, you could see what it’s all about on the screenshot where I had run the CalculatorSpec by JUnit4 based runner. From the other side the plugin allows to run selected specification group and that option does not exist with running by JUnit 4. So you have to select what you want to use within your IDE. On the screenshot you could also notice except Spek runner also JUnit Vintage and JUnit Jupiter runners. That’s because I have added dependencies to Spek, JUnit4 and Junit5 runners. On the GitHub repo with source code exists some examples with defined tests under those runners that you could compare how define test for each one.

Ok, so let’s take a look a little deeper on the technical side of the Spek. As I mentioned before the CalculatorSpec extends from the open class Spek. As the constructor parameter the Spek class takes the function literal with receiver. What it is? To explain it we have to say something about the higher order functions and lambdas on Kotlin.

What is a higher order function. According with Kotlin documentation:

A higher-order function is a function that takes functions as parameters, or returns a function.

So if we have a function type body: () -> Unit it’s supposed to be a function that takes no parameters and returns nothing. Just pure action. For example:

fun execute(body: () -> Unit): Unit {

println("start")

body()

println("stop")

}

execute {

println("function example")

}

// console output:

start

function example

stop

Please take a note that in Kotlin, there is a convention that if the last parameter to a function is a function, that parameter can be specified outside of the parentheses. What is it in this case function literals with receiver? This is a function with a specified receiver object. Inside the body of the function literal, you can call methods on that receiver object without any additional qualifiers. If you have ever written any DSL on Groovy I am sure that you know what it is. If not I encourage you to take a deeper look at Kotlin documentation and examples of their usage of Type-safe Groovy-style builders. You could also read the blog post of the author of Spek framework Hadi Hariri about that (it is a little outdated but still worth to review).

The definition of the Spek abstract class is the following:

abstract class Spek(val spec: Dsl.() -> Unit)Constructor takes function literal where the receiver object is a object implementing Dsl interface. Let’s take a look at Dsl interface itself:

interface Dsl {

fun group(description: String, pending: Pending = Pending.No, body: Dsl.() -> Unit)

fun test(description: String, pending: Pending = Pending.No, body: () -> Unit)

fun beforeEach(callback: () -> Unit)

fun afterEach(callback: () -> Unit)

// fun <T: Spek> includeSpec(spec: KClass<T>)

}There are two important functions. The first one is a group which is responsible for creating a group scope which can contain nested test and/or group scopes.

According to Spek documentation: Spek supports arbitrary number of nested scopes for better grouping of your tests. The second one is a test method and according documentation:

The method creates a test scope, which is equivalent to a test method in JUnit. Based on that two methods the entire specification language is built.

The grouping functions describe, given, context, on and test functions it which are being used on specifications

are defined as extension functions on StandardKt file within the dsl package. The previous versions of Spock were designed a little bit differently and all methods were on the

DescribeBody interface but I think the current state is better.

That kind of design give us the easy way to prepare own extensions. I would say that this is a great example of one S[O]LID principles: open for extension but closed for modification.

So let’s say that I prefer patter given -> when -> then. I could always add my extension methods like that (unfortunately the when is a part of Kotlin syntax so I have to use quotes):

fun Dsl.`when`(description: String, body: Dsl.() -> Unit) {

group("when $description", body = body)

}

fun Dsl.then(description: String, body: () -> Unit) {

test("then $description", body = body)

}And my specification:

given("simple calculator") {

val calculator = Calculator()

`when`("calculating the sum of 2 and 2") {

val result = calculator.add(2, 2)

then("should return 4") {

assertEquals(4, result)

}

}

}Spek also provides beforeEach and afterEach fixtures, which allows running arbitrary code before and after a test, respectively. Every group scope can declare an arbitrary number of fixtures, the order they are executed is based on the order they are declared.

In order to ignore specific group of tests each method have a counterpart prefixed with x (e.g. xdescribe, xit, etc.), which will Spek ignore when executing the spec (on the previous versions were methods prefixed with f which runs only selected method but were deleted on 1.0 release).

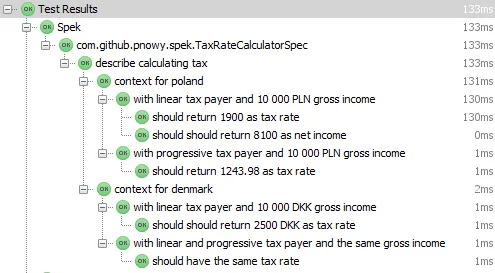

Let’s try to run different specification. For this case I have prepared example class TaxRateCalculator which takes some CountryTaxStrategy and for specific TaxPayer counts the tax rate. What is important the ‘production’ code has been written on the pure Java. You will find the entire source code on my github project.

class TaxRateCalculatorSpec : Spek({

describe("calculating tax") {

val calculator = TaxRateCalculator(PolandTaxStrategy())

context("for poland") {

calculator.taxStrategy = PolandTaxStrategy()

with("linear tax payer and 10 000 PLN gross income") {

val taxPayer = TaxPayer(TaxType.LINEAR, ofPln(10000.00))

val calculatedTax = calculator.calculateTax(taxPayer)

should("return 1900 as tax rate") {

assertThat(calculatedTax.tax).isEqualTo(ofPln(1900.00))

}

should("should return 8100 as net income") {

assertThat(calculatedTax.netIncome).isEqualTo(ofPln(8100.00))

}

}

with("progressive tax payer and 10 000 PLN gross income") {

val taxPayer = TaxPayer(TaxType.PROGRESSIVE, ofPln(10000.00))

val calculatedTax = calculator.calculateTax(taxPayer)

should("return 1243.98 as tax rate") {

assertThat(calculatedTax.tax).isEqualTo(ofPln(1243.98))

}

}

xwith("progressive tax payer and high gross income") {

todo({ "implement" })

}

}

context("for denmark") {

calculator.taxStrategy = DenmarkTaxStrategy()

with("linear tax payer and 10 000 DKK gross income") {

val taxPayer = TaxPayer(TaxType.LINEAR, ofDkk(10000.00))

val calculatedTax = calculator.calculateTax(taxPayer)

should("should return 2500 DKK as tax rate") {

assertThat(calculatedTax.tax).isEqualTo(ofDkk(2500.00))

}

}

with("linear and progressive tax payer and the same gross income") {

val grossIncome = ofDkk(12345.67)

val payerFirst = TaxPayer(TaxType.LINEAR, grossIncome)

val secondPayer = TaxPayer(TaxType.PROGRESSIVE, grossIncome)

val taxForFirstPayer = calculator.calculateTax(payerFirst)

val taxForSecondPayer = calculator.calculateTax(secondPayer)

should("have the same tax rate") {

assertThat(taxForFirstPayer.tax).isEqualTo(taxForSecondPayer.tax)

}

}

}

}

})With this simple example we could see the power of the specification by example especially if we have legacy code and we have to get the

knowledge about business logic behind it. We could easily read the test and we know what’s going on. Also we could define our internal specification

language parts (see new groups and test expressions the above example like with and should) and even we could adjust it to our domain if

it will be needed (but of course with some constrained set within our organization).

In my opinion it is much easier that some testTaxRate method. See the Intellij test runner view:

On the last release appeared also some experimental features regarding subject for test. By default the each test get their own unique instance of the subject but it could be changed and with cache mode set to GROUP the subject will be shared throughout the group which it was declared. That feature supports also subclassing testing - you will find more on the Spek documentation.

class CalculatorSubjectSpec : SubjectSpek<Calculator>({

subject { Calculator() }

//subject(CachingMode.GROUP, { Calculator() })

on("calculating the sum of 2 and 2") {

val result = subject.add(2, 2)

it("should return 4") {

assertEquals(4, result)

}

}

})As a short summary I could say that for now Spek has some lacks. It would be good to have the support for data driven testing, spring integration, etc. - those features which are available on the Spock. But I believe on the future those gaps will be filled and Spek gathers wider scope of usage on Kotlin and Java world.